Definition:

Opal n. an amorphous form of hydrated silicon dioxide that can be of almost any colour. It is used as a gemstone. [from Greek Opthalmios, ‘the eye stone’ or ‘eye lotion’; from Latin Opalus, Gk. Opallios ‘to see a change’, from Sanskrit Upala ‘precious stone’] – Opaline adj.

In Greek mythology Zeus became king of the gods when he defeated the Titans.

Legend has it, having defeated the Titans, Zeus wept joyous tears that turned into Opals upon hitting the ground.

Opal was a favourite gem amongst the ancient Greeks and Romans, many writers of the classical period refer to it.

The source of Precious Opal was long thought to be India, however this now seems unlikely and there are various known occurences of common opal in the Near East and Europe.

Orpheus – One of the Argonauts from Herodotus’ Iliad, the greatest musician and poet of Greek myth:

Orpheus – One of the Argonauts from Herodotus’ Iliad, the greatest musician and poet of Greek myth:

Opal fills the heart of the gods with joy.

According to Orpheus, “On Olympus the Opal was the delight of the immortals, So fair to view that it charmed the strong eye and strengthened the weak.”

Onomacritus (520-485BC) – An Athenian who according to Aristotle was the real author of some of the Greek religious poems which went under the name of Orpheus. Banished from Athens by his patron Hipparchus for making an interpolation in an oracle of Musaeus. He fled to Persia where the Peisistratids, who had also been expelled, employed him to persuade Emperor Xerxes to invade Greece by reciting to him all the Ancient oracles.

The delicate colours and tenderness of Opal remind me of a loving and beautiful child

To the ancients it was known as paederos, the derivation of this meant both ‘child’ and ‘favourite’ – inferring that it had the kind of peerless beauty of a child.

To the ancients it was known as paederos, the derivation of this meant both ‘child’ and ‘favourite’ – inferring that it had the kind of peerless beauty of a child.

The early Greeks believed Opal gave its’ wearer the power of foresight and prophecy.

The Romans called Opal the Cupid Stone and believed they instilled purity and hope.

Plato (427-347BC) in the discourse of his Republic relates the story of Gyges who found a ring that made him invisible and thus allowed him to steal both queen and crown, this may be from whence opal’s reputation as the ‘stone of thieves’ first sprang. Opal was credited with the power to simultaneously strengthen one’s sight and make the wearer invisible.

Gyges, a shepherd in the service of the King of Lydia, one day witnessed a violent storm followed by an earthquake which opened up a deep chasm in the earth near the place where he tended his flock. Curious, he descended into the chasm and saw therein a hollow, brazen horse, with openings at the side. Within the horse lay the body of a huge man and a golden Opal ring glittered on the corpse’s finger. The shepherd removed the ring and took off. Several days later the shepherds assembled to prepare their monthly reports to the king. As Gyges sat with the others he carelessly turned and twisted the Opal ring he now wore, until by chance, he turned the bezel toward the inside of his hand. Immediately he became invisible yet when he turned the ring around again he reappeared. Repeating the experiment several times confirmed the strange virtue of the ring. Realizing then the extraordinary powers the Opal ring afforded him the shepherd asked and obtained the privilege of bearing reports to the king. He soon found means to seduce the queen, and with her aid, to slay the king and gain possession of the throne.

Ancient Greek philosopher and naturalist Theophrastos (372-287 B.C.) prepared Peri Lithon (‘ On Stones’) about 315BC, the oldest existent treatise to classify rocks and minerals based on their behaviors and common properties. Theophrastus refers to ?p?????? or ‘Opal’, he provides the quote of Onomacritus and perhaps even the tradition of regarding Opal as female derives from his dividing gemstones into male and female. Pliny the Elder makes clear references to his use of On Stones in his Historia Naturalis of 77 AD. From both these early texts was to emerge the science of mineralogy, and ultimately geology.

Pliny the Elder (23-79AD) was a commander of the Roman cavalry in Germany, in his retirement he wrote the 37 volume encyclopaedia Historia Naturalis, perhaps the foremost authority on gemstones in the ancient world, his treatise are still relevant today . Pliny calls India the mother of Opal, yet he is referring to the finest quality then available as he also mentions Opal found in Egypt, Pontus, Galatia, Thasos and Cyprus. Pliny documented the easy detection of basic foiled-glass Opal simulants, examples of which feature in jewels made nearly two millennia after his death.

Pliny the Elder (23-79AD) was a commander of the Roman cavalry in Germany, in his retirement he wrote the 37 volume encyclopaedia Historia Naturalis, perhaps the foremost authority on gemstones in the ancient world, his treatise are still relevant today . Pliny calls India the mother of Opal, yet he is referring to the finest quality then available as he also mentions Opal found in Egypt, Pontus, Galatia, Thasos and Cyprus. Pliny documented the easy detection of basic foiled-glass Opal simulants, examples of which feature in jewels made nearly two millennia after his death.

“It is made up of the glories of the most precious gems; to describe it is a matter of inexpressible difficulty. There is in it the gentler fire of the Ruby, the brilliant purple of the Amethyst, and the sea-green of the Emerald, all shining together in an incredible union. Some aim at rivalling in lustre the brightest azure of the painter’s palette, others the flame of burning sulphur, or of a fire quickened by oil.”

The ancients believed that if a person wore the precious stone which, according to their tradition, was in affinity with the planets and the month of their birth, they would have protection against their enemies, sickness, accident, or even death.

The Orientals referred to Opals as “The Anchor of Hope”.

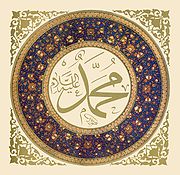

In the time of the prophet Muhammad (ca.570 Mecca – 632 Medina) his people were enamoured of Opal and according to Arabian folklore “Opals are the remnants of lightning strikes to the ground, and the flashes in the stone are captured lightning.”

According to Indian legend, the origin of the Opal lies in a feud between the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva who once vied in jealous love for a beautiful woman. This angered the Eternal, who changed the fair mortal into a creature made of mist. Each of the three gods then endowed her with his own colour so as to be able to recognise her. Brahma gave her the glorious blue of the heavens, Vishnu enriched her with the splendor of gold, and Shiva lent her his flaming red. Alas, all this was in vain, since the lovely phantom was whisked away by the winds. Finally, the Eternal took pity on her and transformed her into a stone, the Opal, that sparkles in all the colours of the rainbow. – ‘Birthstones and the Lore of Gemstones’ by Willard Heaps

According to Indian legend, the origin of the Opal lies in a feud between the gods Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva who once vied in jealous love for a beautiful woman. This angered the Eternal, who changed the fair mortal into a creature made of mist. Each of the three gods then endowed her with his own colour so as to be able to recognise her. Brahma gave her the glorious blue of the heavens, Vishnu enriched her with the splendor of gold, and Shiva lent her his flaming red. Alas, all this was in vain, since the lovely phantom was whisked away by the winds. Finally, the Eternal took pity on her and transformed her into a stone, the Opal, that sparkles in all the colours of the rainbow. – ‘Birthstones and the Lore of Gemstones’ by Willard Heaps

In Fourteenth Century India a belief grew that one could pass an Opal across the brow to clear the brain and strengthen the memory.

Sources & Image Credits:

JEWELLERY OF THE ANCIENT WORLD, Jack Ogden, 1982. (Pliny on Opal and imitations)

THE CURIOUS LORE OF PRECIOUS GEMSTONES, G.F.Kunz,1913;1971.

THE GREAT BOOK OF JEWELS, Ernst A. & Jean Heiniger, 1974.

THE – OPAL AUSTRALIA’S ‘QUEEN OF GEMS’, F.A Newman – Gem Specialists Melbourne, printed in “The Argus” 25 October 1924. (Onomacritus & Orpheus quotes)

RINGS FOR THE FINGER, George Frederick Kunz, 1917;1973. (pages 290-291: Plato and the Opal ring of Gyges)

THE POWER OF GEMSTONES, Raymond J.L.Walters, 1996.

THE STORY OF NOBLE OPAL, Sydney B.J. Sketcherley, 1908.

OPAL – THE PHENOMENAL GEMSTONE, Lithographie, 2007.